Chloe Chayo‘s research paper for ECO475 was runner up for the Arthur Hosios Scholarship in Economics. Applied Econometrics II continues from ECO375, but in this course the regression model is extended in several possible directions: time series analysis; panel data techniques; instrumental variables; simultaneous equations; limited dependent variables. Students complete a major empirical term paper, like Chayo’s below, that applies the tools of econometrics to a topic chosen by the student.

The essay not only exhibits a high standard of research rigour and excellent writing, but the choice of topic serves as an example of the immediate relevancy of economics research. Undergraduate students have the opportunity to examine the real world around them using the tools of econometrics. The Ontario Legislature passed the Pay Transparency Act six years ago. During the 2022-2023 academic year, Chayo examined its impact of the gender wage gap here in the province.

Private but Transparent: Pay Transparency and the Gender Wage Gap

Abstract

This study concerns the wage gap between men and women. It investigates Ontario’s Pay Transparency Act, passed in April 2018, to ask how does pay transparency impact the gender wage gap? Leveraging Canada’s Labor Force Survey data from 2015 to 2020, an event-study research design finds pay transparency reduces the gender wage gap in hourly wages by 32 to 41 cents per hour on average, representing 6 to 8 percent of the wage gap in Ontario’s private sector. This statistically significant result is robust to a host of provincial, temporal, and individual characteristic controls.

Introduction

In Canada, on average, women have historically earned less than men, when looking at both total earnings and hourly wages. Although this gap has narrowed over time, an increasing share of the gender wage gap cannot be explained by differences in education, hours worked, industry and job roles (Baker and Drolet 2010). The gender wage gap is a concerning policy issue, addressed repeatedly through legislation, starting with Canada’s first pay equity policy in 1977. This paper will focus on the effects of Ontario’s Pay Transparency Act, passed on April 26 2018. The Pay Transparency Act (henceforth, Act) is centered around regulating employers asking about a candidate’s undisclosed compensation history and anti-retaliatory behavior for compensation-related inquiries. It requires all employers, regardless of firm size, to include a range of expected compensation for advertised job postings. It also requires companies with 100 employees or more to produce yearly pay transparency reports, to be submitted to the Ministry of Labor and posted online. It is the first private sector legislation of its kind to be passed in Canada.

This study will therefore ask how does pay transparency impact the gender wage gap? This study finds that the Ontario Pay Transparency Act reduced the gender wage gap in hourly wages by approximately 41 cents per hour in the Ontario private

sector. This statistically significant result still holds when a difference-in-difference-indifferent model is implemented to compare the Ontario private sector to the private sector in the rest of Canada, but the gender gap reduction falls to 32 cents an hour. Respectively, these reductions signify 8 and 6 percent of the Ontario gender wage gap. Heterogeneous policy effects were assessed per occupation, where there was a statistically significant reduction in the wage gap only only in education, law, and social, community and government services alongside occupations in natural resources, agriculture and related production. Heterogeneity was also explored for individuals in Ontario with and without children below the age of 5. For those with children, the policy effect was larger than the average population, showing a reduction of 68 cents per hour, and those without children did not face a statistically significant policy effect. Robustness checks which vary time trend controls and replicate this study’s regression in the rest of Canada and the Ontario public sector find no change in the wage gap, providing strong support for the effectiveness of pay transparency as a means of closing the gender wage gap.

The effect of pay transparency on the gender wage gap is a relevant question because, first, it concerns roughly half of the Ontario population – women – illustrating how this policy issue is impactful. Regardless of partisanship, equal gender pay has been a political priority in government. At both the provincial and federal level, ways of promoting gender equality in labor markets have been extensively discussed, so the findings of this study will help continue to inform policy proposals, promoting the implementation of the most efficient policy to achieve gender equality in compensation. Internationally, closing the gender wage gap is included in the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal of gender equality, which Canada has included in its 2030 National Agenda Strategy (Canada 2019). Closing the gender wage gap is also implied in various international agreements that Canada has signed, such as the International Labor Organization Convention 100 on equal remuneration. Therefore, this study is relevant as it studies a phenomenon that concerns a wide proportion of the Canadian population, will help inform policy choices at various levels of government, and is linked to Canadian priorities and commitments to international treaties for development.

1 Literature Review

The gender wage gap has always existed in Canada. Scholarship has pointed at differences in education, gendered occupational choices, field selection and the child penalty to explain the gender wage gap. Using hourly wages in the Labor Force Survey for private sector employees across Canada, Schirley (2015) found that the gender gap has narrowed from 1997 to 2014 across all provinces, and that most of the wage gap comes from gender differences in industry and occupation. Baker and Drolet (2010) have confirmed the sustained female progress, but instead argue that an increasing share of the wage gap is unexplained by the above factors. Baker and Drolet (2010) also draw the distinction between the gender gap in wages versus earnings, concluding that wages are the best measure for the gender gap as they describe the price of labor instead of individual, gendered choices on labor hours (Baker and Drolet 2010).

Recent scholarship has pointed at the role of compensation negotiation as a cause for the gender wage gap, starting with Recalde and Vesterlund (2020). Pay transparency legislation aims to close the gender gap by promoting female negotiation. Babcock et al (2006) found with survey evidence that men are two to four times more likely to start salary compensation negotiations compared to women. These findings have been complemented by Leibbrandt and List, who confirmed men are more likely to negotiate their pay when there is no explicit statement for negotiation, but that negotiation differences vanish across genders if job postings mention the possibility of salary negotiation (Leibbrandt and List 2015).

Existing studies have found promising effects for pay transparency as a policy to decrease the gender wage gap. Baker et al studied the effect of public employee pay transparency legislation in 1996 on the gender wage gap for university faculty employees, using data from Statistics Canada’s University and College Academic Staff System, for 1989 to 2018. Leveraging heterogeneity in when public employee pay transparency came into effect for public employees across provinces, Baker et al (2019) found that pay disclosure significantly reduced the gender gap by 1.2 to 2 percentage points. Increased female bargaining is a mechanism through which this reduction takes place, but so is a reduction in male wage growth. Recalde and Vesterlund (2020) confirm the positive effect of pay transparency on female compensation. Bennedsen et al (2019) found that the 2006 pay transparency law in Denmark reduced the gender gap by two percentage points, but by slowing the wage growth for male employees instead of prompting female wage growth.

However, the effects of pay transparency must be studied further, as the gender gap may be perpetuated if men use pay information to bargain for compensation while women do not (Baker et al 2019). Additionally, the effects of pay transparency can be mixed: although pay transparency can close the gap across co-workers, average wages may lower within a firm if spillovers between negotiations force employers to bargain aggressively (Cullen 2023). Negotiating might be harmful for women as it poses opportunity costs, has the potential for future backlash and decreases the chances of successful future negotiations (Exley et al 2020). Across firms, pay transparency can increase wages for lower-skill work by reducing information rents in monopsony settings (Cullen 2023).

Therefore, existing literature illustrates how the effect of pay transparency on the gender wage gap can still be explored. Initial expectations of this study are that pay transparency will close the gender wage gap by reducing differences in negotiation across genders, as suggested by Leibbrandt and List (2015) and Recalde and Vesterlund (2020). This would also be in line with the public sector results of Michael Baker et al (2019). Still, pay transparency may have no effect if negotiation increases are homogenous, which may be the case in the private sector unlike the public sector. Based on the evidence from Exley et al (2020) and Cullen (2023), the gender gap could be perpetuated, especially because the mechanisms they describe – employer bargaining in retaliation, or female-specific opportunity costs to negotiation – may be more prominent in the private sector than the public sector.

2 Empirical Model

First, this study’s models rely on intention to treat assumptions. Prior to starting my analysis, I assume that firms did not previously have pay transparency and complied with pay transparency measures proposed by the Act. There is also a gap between the date the policy was announced, April 2018, and when it came into effect in January 2019. To fully capture the policy effect, I consider the policy to be enacted on its day of announcement, as it is highly likely that firms display anticipatory behavior. Pay transparency and the new hiring procedures it involves take time to implement, so firms had to be sure they were compliant by the date the policy came into effect, making it very likely that firms implemented measures before January 2019. This way, I can be sure to capture the policy effect if I count the policy to be enacted on the date it was announced.

The gender gap will be looked at using a continuous hourly wage earnings measure. This variable exists for all employees in the Labor Force Survey, regardless of whether their pay structure is based on hourly wages or salaries. Performance-related bonuses are excluded in this measure. This preference for hourly wages over total earnings is a better measure of the price of labor, as total earnings are a function of the price of labor (hourly wage) alongside choices on hours worked, which vary by gender.

This approach focuses on wages instead of earnings to avoid capturing genderspecific choices on hours worked, where men tend to work more hours than women (Baker and Drolet 2010) as they are less likely to be subject to social norms which assign domestic work and child caring to women. The analysis will focus on private sector earnings as this will give the most direct effect of policy. I recognize there could be spillovers to the public sector as part of strategic behavior, but the public sector has existing pay transparency legislation (such as that passed in 1996) whereas the Act is the first private sector legislation of its kind in Canada.

Next, I implement controls for existing time trends and other characteristics known to affect the gender wage gap, such as marital status, occupation, economic family type (which captures the presence of children, whether a household is single- or doubleparent, and who is the main provider), education and age.

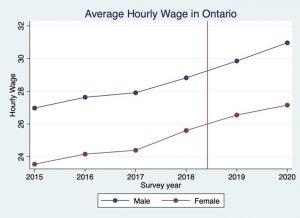

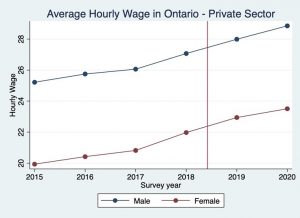

Using a difference-in-difference is appropriate due to the presence of parallel trends across Canada (Table 1 and Figure 5), Ontario (Figure 1) and Ontario’s private sector (Figure 2). Figures 1 and 2 show that, prior to the Act, male and female wages were trending parallel, suggesting that, absent any policy intervention, they would have continued trending at the same rate. This validates the use of my empirical model. To further control for time trends, I also implement gender-year fixed effects in some specifications, as this nets out baseline differences in wages over time within Ontario, such as wage growth due to inflation, helping to better isolate the effect of pay transparency policy.

I propose the following regression:

![]() (1)

(1)

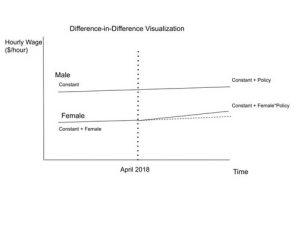

Here, Yit are hourly wages. αi represents individual fixed effects alongside controls for occupation, marital status and economic family type, δtW represents year or genderyear fixed effects, Pt is a dummy variable indicating whether the pay transparency policy is in place (Pt = 1 after April 2018) and Wi is an indicator variable for women. θ represents the pre-policy wage gap. β represents the causal effect of the policy on male wages, while β + γ represents the policy effect on female wages. The main coefficient of interest is γ, as it represents the differential effect of the policy on female wages compared to male wages. This is summarized in Figure 3, which is a simplified replication of Figure 2. The value of γ will give the average treatment effect, that is the average effect of the policy across Ontario’s private sector, but it is possible that pay transparency has heterogeneous effects across the population. As such, the above model will be repeated for sub-sections of the Ontarian population, such as individuals with and without children younger than the age of 5, and those working in the same occupation. Later, robustness checks include running the above model for Ontario’s public sector and the rest of Canada, as all other Canadian provinces have not implemented similar legislation.

This first approach, though robust to Ontario-specific shocks, is insufficient to validate the effects of pay transparency alone as it cannot discard the possibility of a nation-wide narrowing of the gender wage gap that is unrelated to the existing controls and pay transparency policy. To solve this, I then implement a triple-difference design, using four specifications with incremental individual characteristic, temporal and geographic controls.

This model aims to capture the effect of the policy on Ontario’s private sector wage gap compared to the rest of Canada’s private sector wage gap. This is represented by the following equation:

Yit = αi+δt+θWi+βPt+πTi+ςPt∗Wi+λPt∗Ti+ηTi∗Wi+γWi∗Pt∗Ti+ϵit (2)

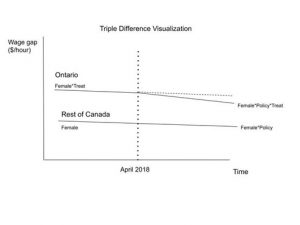

Yit, αi, Wi and Pt are the same as in the first model implemented. δt still represents time trends, but is now province-year fixed effects. Next, I incorporate Ti, an indicator for Ontario, which is the treatment province. The coefficient on Wi alone gives the wage gap in the rest of Canada, while the coefficient on the interaction between Wi and Ti shows the difference between the wage gap in Ontario compared to the rest of Canada. The coefficient, ς , on the interaction between Wi and Pt gives the change in wage gap in the rest of Canada after the policy, and therefore represents all non-policy related changes on the wage gap. With this,γ is the coefficient of interest from the interaction between Wi, Pt and Ti. γ therefore represents the effect of pay transparency on female wages in Ontario’s private sector compared to the rest of Canada’s private sector, after controlling for baseline differences across provinces and individual characteristics (including education, age, occupation, marital status, economic family type). The expectation is that γ is positive, as this would reflect pay transparency narrowing the gender wage gap.

This approach is summarized in Figure 4, which plots a simplified visualization of the wage gap over time, labeling the respective coefficients explained above. For simplicity, Figure 4 is plotted as a difference-in-difference, as the y-axis is in terms of the difference between male and female hourly wages (the wage gap).γ appears to be negative but this is due to the choice of the wage gap on the y-axis, which was made

to facilitate the visual representation of the difference-in-difference-in-difference.

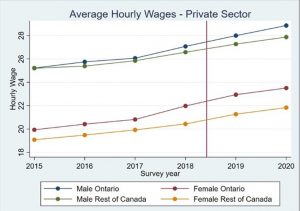

For this approach to be valid, the same assumptions for the difference-in-difference above must hold, and they do. Parallel trends in Canada are confirmed by Statistics Canada, which shows only a 2 percentage point reduction in the gender wage gap from 2015 to 2020 (Statistics Canada 2022), amounting to $4.13 dollars in 2018 (Pelletier et al 2019), and Figure 2, summarizing time trends for male and female wages in Ontario’s private sector. Figure 5 also shows parallel pre-trends by plotting the average private sector hourly wages for men and women, in Ontario and in the rest of Canada, over time. Prior to 2018, parallel wage trends can be seen. This allows for the use of a triple difference.

The use of a difference-in-difference-in-difference will provide further strength to finding the causal impact of pay transparency, as this approach controls for Canadawide effects on wages, such as inflation and pre-policy time trends. This model isolates the effect of pay transparency, netting out any other potential wage shocks that are not directly controlled but occur Canada-wide. Combined with the difference-in-difference model, finding consistent policy effects with these models, that are at least in the same direction, but ideally have similar magnitude too, will provide strong evidence for the effect of pay transparency on the gender wage gap, as province- and nation-wide unobservables are accounted for.

3 Data

I use Canada’s Labor Force Survey from January 2015 until March 2020. Each month is a repeated cross section across all Canadian provinces, yielding 6,316,150 observations, where the unit of observation is an individual-year. The Labor Force Survey contains data at the individual level on labor market characteristics, such as employment, hourly wages as a continuous variable, worker occupation, industry, size of firm employed and demographic data, like gender, marital status, immigrant status, age, education and parent status (economic family type). The occupation categories used in this analysis are summarized in Table 13. My data set merges Labor Force Survey data, collected each month for every year, and therefore represents a repeated cross-section of the Canadian population.

I will stop my analysis before COVID-19, as its strong labor market impacts may hinder this study’s primary focus: the progression of the gender wage gap as a result of pay transparency legislation in Ontario. Filtering for employed individuals in the private sector in Ontario yields 654,902 observations out of 1,736,737 observations representing employed individuals in Ontario.

Average hourly wages in Canada were $24.69 in 2015 and rose to almost $28 in 2020. This is depicted in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 then show summary statistics for hourly wages in Ontario, by gender. In Ontario, men earn above the national average, starting at approximately $27 dollars in 2015 to almost $31 in 2020. Female hourly wages in Ontario are about 3 dollars less than male hourly wages, starting at $23.50 in 2015 and rising to about $27 in 2020. There are more women working than men in Ontario, but the difference is small. Limiting the sample to Ontario’s private sector only yields Tables 4 and 5, with male and female average wages respectively. In Ontario’s private sector, there are slightly more men than women working. As expected, male earnings are higher on average than female earnings. In 2015, male hourly wages were $25/hour on average, rising to $27/hour in 2018 and finally to almost $29/hour in 2020. For women, the average wage was $20/hour in 2015, then $22/hour in 2018, and $23.50/hour in 2020. There is less variation for female wages than there is for male wages, as seen by the smaller standard deviations in Table 5 compared to Table 4. The minimum values between $2 and $3 dollars in Tables 1 to 5 do not seem to be compliant with minimum wage legislation in Ontario and beyond, but these abnormalities do not detract from the main analysis.

The gender wage gaps in Ontario are summarized in Table 6. The gender wage gap has remained relatively stable from 2015 to 2020, although it is larger in the private sector. The gender gap in hourly wages is about $3 per hour in Ontario overall, which is in line with the $3.79 gap in Canada (Statistics Canada 2022), and the wage gap increases to $5 per hour in Ontario’s private sector, meaning it is higher than both the provincial and national average.

Figures 1 and 2 plot a time trend of average male and female wages in Ontario and the Ontario private sector, respectively, from 2015 to 2020. Both figures illustrate how, pre-policy, the gender wage gap was closing, and it continued to do so after the pay transparency policy was implemented, leaving the open question of whether pay transparency helped close the gender wage gap. Figures 1 and 2 display parallel trends, which validates the use of difference-in-difference models as an empirical strategy as they illustrate meeting the parallel trend assumption for Ontario broadly and the Ontario private sector specifically. Figure 5, which plots Canada-wide wages over time by region and gender, illustrates how hourly wage time trends for men and women are similar in Ontario compared to the rest of Canada. It also shows how Ontario residents have higher wages compared to individuals who do not live in Ontario, regardless of gender.

4 Results

4.1 Main Results

Statistical analysis finds that pay transparency is shown to reduce the gender wage gap by approximately 32 to 41 cents per hour on average in Ontario. These results are robust to various controls including marital status, occupation, economic family type, age and education. These results are summarized in Tables 7 and 8. Table 7 has 4 specifications of a difference-in-difference. Column one has no time controls but controls for marital status and economic family type, and finds the introduction of pay transparency reduced the gender wage gap in hourly wages by 21 cents an hour. This result is statistically significant at the 0.1% level. Next, column 2 incorporates a time trend, representing female wage growth patterns that continue after the policy, and finds the same policy effect of reducing the wage gap by 21 cents per hour, significant at the 0.1% level. This reduction in the wage gap amounts to 4 percent of the difference in average female and male wages in 2019, which was $5.05 as shown in Table 6.

21 cents is equivalent to approximately a 1% increase in the average female wage in 2019, which was about $23 in 2019, as shown in Table 5. This result is economically significant, as a 21-cent rise in the female wage rate accounts to $437 extra income a year, assuming a 40-hour work week. Columns 3 and 4 in Table 7 incorporate genderyear fixed effects and show that the policy effect is robust to differences in wage due to occupation. Adding gender-year fixed effects in Column 3 suggests that the policy effect is larger than in specifications 1 and 2, yielding a reduction in the gender wage gap by 47 cents per hour, which represents 9% of the gender wage gap. When adding occupation controls, this effect remains large at 41 cents an hour, or 8% of the pay gap. Both these results are statistically significant at the 1% level. There is a reduction in the number of observations when adding occupation controls as this variable only exists from 2017 onward. Columns 1 and 2 in Table 11 interact occupation and policy, then occupation and year as fixed effects, respectively. With these varying controls, the policy effect persists at approximately 41 cents per hour. This is economically significant, as it represents an additional $853 dollars of income for women working 40 hours a week.

The policy effect on male wages may be ambiguous. Columns 1 and 2 suggest the policy led to a statistically significant increase in the male wage rate by about $2 per hour, but this increase becomes statistically insignificant with the addition of genderyear fixed effects and occupation controls in columns 3 and 4. As such, it is most likely that pay transparency narrowed the gender wage gap by promoting female wage growth, potentially through female negotiation, as suggested by the findings in the Literature Review.

Still, with only the results in Table 7, it is possible that these effects on the wage gap are attributed to another factor that is not the Act nor is captured by the existing time and individual characteristic controls in place. Table 8 rejects this notion by conducting a triple difference design exclusively in the private sector, where the parameter of interest is the triple interaction between indicator variables for female wages, policy implementation and being in the Ontario private sector. Column 1 has no controls, while Column 2 onwards includes province-year fixed effects. Column 3 and 4 add individual characteristic controls. Overall, these specifications verify the persistence of female wages below male wages on average across all of Canada, with Ontario’s private sector female wages being, on average, about half a dollar above the rest of Canada’s private sector. This is potentially due to wage level differences across provinces. Across all specifications, the policy effect on closing the gender wage is consistent at about 32 cents per hour in Ontario, and is statistically significant at the 0.1% level. Column 4 confirms policy effect is robust to marital status, economic family type, occupation, education and age controls. A closing of the wage gap by $0.32/hour accounts for 1.4% of average female private sector wages in Ontario, and roughly 6% of the total private sector gender wage gap in Ontario. For women working full-time, this increase in hourly wages is estimated to increase yearly earnings by $665. This result is therefore economically significant. The closing of the gender wage gap as a result of pay transparency persists when replacing province-year fixed effects for gender-year fixed effects, this can be found in Table 12.

However, how the wage gap is closing remains an open question based on the results of Table 8. The coefficients on the policy-treatment interaction indicates male wage growth in Ontario was between 23 to 40 cents per hour, statistically significant at the 0.1% level. This means that the $0.32 increase described previously as the closing of the gender wage gap is female wage growth above the wage increase faced by men in Ontario. With this, it is not possible to unambiguously determine how the wage gap is closing, as it could equally promote female wage growth or slow male wage growth, or a combination of both. Still, this discussion is tangential to this analysis, whose first priority is to establish the effect of pay transparency on the size of the gender wage gap. Another interesting trend is that, after the inclusion of individual characteristic controls in columns 3 and 4, female wages in the rest of Canada’s private sector are estimated to have decreased by 10 cents per hour, significant at the 1% level. This further strengthens arguments in favor of pay transparency as a cause for the narrowing of the gender wage gap, as provinces that did not pass pay transparency legislation saw a widening of the gender wage gap after accounting for province-level differences and a host of individual-level factors.

4.2 Heterogeneous Policy Effects

Furthermore, now that a policy effect can be established with confidence, heterogeneous effects of pay transparency will be explored. Are there any groups that systematically see a different effect than the average policy effect found in Ontario’s private sector? Table 9 splits Ontario’s private sector into individuals with and without children 5 years old or younger. Column 1 applies the same specification as Column 3 in Table 7 to people without children, and column 2 does the same for those with children. As expected, the pre-policy gender wage gap is greater for individuals with children than for those without, as given by the statistically significant coefficients for the indicator variable indicating women. Before the Act, women without children earned about $1.50/hour less than their male counterparts, while women with children earned approximately $2.40/hour less than men with children, after accounting for time trends and wage differences from marital status and economic family type. After controlling for marital status, economic family type and including gender-year fixed effects, there is no statistically significant policy effect on the gender wage gap for individuals without children. However, for individuals with children, pay transparency is associated with an even larger narrowing of the gender wage gap compared to the average effect on the total population (found in Tables 7 and 8). Pay transparency is associated with a reduction of the wage gap by almost $0.70/hour. This result is highly statistically significant at the 1% level, while also being extremely economically significant. 70 cents accounts for almost 3% of the average wage for women with children, and almost 14% of the total gender wage gap in Ontario’s private sector. In a year of work, assuming a 40-hour work week, this means $1456 in additional yearly income for recent mothers. This provides evidence for pay transparency benefiting recent mothers more than average women, as the lack of statistical significance for the coefficient on the policy indicator variable suggests no effect of pay transparency on male wages, thus implying that pay transparency closes the wage gap among parents of young children by promoting wage growth for recent mothers.

In addition, Table 10 attempts to look at heterogeneity in closing the gender gap per occupation. Only occupations in education, law, government services and those in natural resources, agriculture and related production occupations saw a statistically significant difference in the wage gap after the Act was enacted. Table 13 maps column numbers to occupation groups. These are the same occupation categories used as controls in all other specifications that have occupation controls. For occupations in education, law and government services, policy implementation is associated with a massive $2.58 narrowing of the wage gap; this result is statistically significant at the 5 percent level. It is possible that this result stems from this occupation’s closeness to public sector jobs, which have already implemented pay transparency. It may also be an occupation-specific shock. Occupations in natural resources and agriculture saw a similar, sizable and statistically significant narrowing of the wage gap of $2.37. A more detailed understanding of how pay transparency is implemented in these occupations, alongside their gender composition over time, is required to fully interpret these results. All other occupations do not show statistically significant policy effects. Still, both positive coefficients per occupation help support the hypothesis that pay transparency closes the gender wage gap, although more work must be done to look at occupationspecific trends to better understand these findings. These results also further suggest that pay transparency may close the wage gap across occupations more than it does within occupation.

4.3 Assessing Robustness

Moreover, robustness checks are conducted in Table 11, helping to further establish the effect of pay transparency in closing the gender wage gap. When varying time trends and interacting occupation with policy, then occupation with year for fixed effects in Columns 1 and 2 respectively, the policy effect persists at about 40 cents per hour. Column 3 repeats the difference-in-difference specification with Ontario’s public sector, and Column 4 repeats it with the rest of Canada, with the same controls for marital status and economic family type. The coefficient of interest on the policy female interaction is statistically insignificant. This suggests there was not a significant closing of the gender wage gap in the Ontario public sector nor rest of Canada at the time the Pay Transparency Act was passed. This strengthens the argument for the effectiveness of pay transparency legislation to close the gender wage gap, as it discards the possibility of another factor that is not pay transparency contributing to closing the gender wage gap. The analysis in column 3 with Ontario’s public sector weakens the hypothesis of spillover effects of private sector pay transparency to the public sector, as there seems to be no policy effect for the public sector’s gender wage gap. This potentially may be due to the previously-passed 1996 pay transparency legislation, which yielded results of similar magnitude and direction to those found by this study (Baker at al 2019). The main regressions in Tables 7 and 8 were repeated using the log of hourly wages, and still yielded a statistically significant policy effect.

5 Conclusion

This study has used difference-in-difference and triple-difference models to find the implementation of pay transparency reduces the gender wage gap by 32 to 41 cents per hour on average. This represents 6 to 8 percent of the gender wage gap between men and women in Ontario’s private sector. This causal effect is robust to a host of individual characteristic, geographic and temporal controls. Heterogeneous effects on certain sub-sections of the population may be larger, as recent mothers saw a closing of the wage gap by almost 70 cents per hour. In terms of its academic implications, this study supports other academic findings of the effectiveness of pay transparency in closing the gender wage gap. The policy implication of this analysis is further confirmation of pay transparency as a viable pay equity policy tool, with potentially little to no unintended negative side effects on non-target groups.

Future work can be done to assess what type of pay transparency policies are most effective in closing the wage gap. For instance, only firms with 100 employees or more are required to publish pay transparency reports. It would be possible to separate the Ontario private sector sample by firm size, and compare the policy’s effect for larger firms to the 150,254 observations at firms who have 99 employees or less as these do not have to submit transparency reports. This would help decompose the effect of pay transparency legislation into the effect of pay transparency reports versus publishing expected compensation ranges for advertised jobs, and the other measures that are mandatory for all firms, regardless of size. This was not possible at the time of the writing of this analysis as pay transparency reports had a phased implementation, with the first pay transparency report deadline as May 2020 for firms with over 250 employees, then May 2021 for firms with 100 or more employees. Firms are then required to submit pay transparency reports every year. This heterogeneity in pay transparency report submission can also be leveraged in future to assess heterogeneous impacts of different types of pay transparency measures.

Another potential next step could be further research into the heterogeneous effects of pay transparency at the individual level. With richer individual level data, where the same individuals are followed over time instead of having a repeated cross-section, it would be possible to better answer how the wage gap is closing through pay transparency, whether it slows male wage growth, leads to larger female than male wage growth, or increases only female wages. Similarly, it would be possible to investigate where on the hourly wage distribution the effect of pay transparency is more pronounced. It is possible that pay transparency affects women at the top of the wage distribution more than women in the middle, for instance.

References

- Babcock, L., Gelfand, M., Small, D., & Stayn, H. “Gender Differences in the Propensity to Initiate Negotiations.” Social psychology and economics, 2006, pp. 239–259, Edited by D. De Cremer, M. Zeelenberg, & J. K. Murnighan, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Baker, Michael, Halberstam, Yosh, Kroft, Kory, Mas, Alexandre and Messacar, Derek. “Pay Transparency and the Gender Gap.” National

Bureau of Economic Research, 2019, Working Paper No. 25834, Revised December 2021, http://www.nber.org/papers/w25834.

- Baker, Michael, and Marie Drolet. “A New View of the Male/Female Pay Gap.” Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques, vol. 36, no. 4, 2010, pp. 429–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25782105. Accessed 31 Jan. 2023.

- Bennedsen, Morten, Simintzi, Elena ; Tsoutsoura, Margarita and Wolfenzon, Daniel. “Do Firms Respond to Gender Pay Gap Transparency?” National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2019, NBER Working Paper No. 25435, Revised April 2020,

https://www.nber.org/papers/w25435.

- Bill 3 – Chapter 5: Pay Transparency Act. Province of Ontario. Web. May 17 2018. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/s18005#BK8

- Employment and Social Development Canada. Towards Canada’s 2030 Agenda National Strategy. [Quebec]: Government of Canada, 2019. Government of Canada. Web. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-socialdevelopment/programs/agenda-2030/national-strategy.html

- Cullen, Zoe. “Is Pay Transparency Good?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2023. Working Paper 23-039, January 2023. Harvard Business School. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/23-039 415d7c10-122b-4fec-96b7-3495e55ed0ea.pdf. Accessed 31 Jan 2023.

- Exley, Christine, Niederle, Muriel and Vesterlund, Lise. “Knowing When to Ask: The Cost of Leaning In.” Journal of Political Economy, Vol 128, No 3, March 2020, University of Chicago, https://doi.org/10.1086/704616. Accessed 31 Jan 2023.

- Leibbrandt, Andreas, and John A. List. “Do Women Avoid Salary Negotiations? Evidence from a Large-Scale Natural Field Experiment.” Management Science, vol. 61, no. 9, 2015, pp. 2016–24. JSTOR,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/24551582. Accessed 30 Jan. 2023.

- Pelletier, Rachelle, Patterson, Martha and Moyser, Melissa. “The gender wage gap in Canada: 1998 to 2018” in Labour Statistics: Research Papers. Centre for Labour Market Information, Statistics Canada Centre for Gender, Diversity and Inclusion, Statistics Canada.Catalogue no. 75-004-M, October 11 2019. Ottawa. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-004-m/75-004-m2019004eng.htm#shr-pg0

- Recalde, Maria and Vesterlund, Lise. “GENDER DIFFERENCES IN NEGOTIATION AND POLICY FOR IMPROVEMENT.” National

Bureau of Economic Research, December 2020, Working Paper No 28183, http://www.nber.org/papers/w28183.

- Schirle, Tammy. “The Gender Wage Gap in the Canadian Provinces, 1997-2014.” Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques, vol. 41, no.

4, 2015, pp. 309–19. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43699183. Accessed 31 Jan. 2023.

- Statistics Canada. Labor Force Survey. Ottawa, Ont: Statistics Canada, 2015-2020.

- Statistics Canada. “Pay gap, 1998 to 2021” in Quality of Employment in Canada. Statistics Canada, Catalogue no.14-28-0001-X, May 30 2022, Ottawa. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/14-28-0001/2020001/article/00003-eng.html

6 Tables and Figures

Table 1: Hourly wages for all of Canada, per year

| Year | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| 2015 | 616438 | 24.691 | 12.861 | 2.06 | 153.85 |

| 2016 | 618594 | 25.19 | 13.198 | 2 | 168.27 |

| 2017 | 629418 | 25.592 | 13.258 | 2 | 192.31 |

| 2018 | 621958 | 26.387 | 13.447 | 2.4 | 176.41 |

| 2019 | 611763 | 27.226 | 13.637 | 3 | 115.38 |

| 2020 | 99133 | 27.933 | 14.025 | 3 | 108.17 |

Table 2: Hourly wages for men in Ontario, per year

| Year | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| 2015 | 83066 | 26.974 | 14.394 | 3.06 | 120.19 |

| 2016 | 82971 | 27.634 | 14.864 | 2.02 | 161.54 |

| 2017 | 84283 | 27.91 | 15.044 | 2.4 | 192.31 |

| 2018 | 83666 | 28.82 | 14.745 | 2.49 | 153.85 |

| 2019 | 84980 | 29.851 | 14.885 | 3 | 108.17 |

| 2020 | 13959 | 30.964 | 15.384 | 3 | 108.17 |

Table 3: Hourly wages for women in Ontario, per year

| Year | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| 2015 | 85388 | 23.546 | 12.591 | 3 | 105.77 |

| 2016 | 85720 | 24.16 | 12.949 | 2.02 | 112.09 |

| 2017 | 84763 | 24.395 | 13.073 | 3 | 140 |

| 2018 | 84298 | 25.603 | 12.940 | 3 | 134.62 |

| 2019 | 85474 | 26.548 | 13.303 | 3.07 | 110.19 |

| 2020 | 14222 | 27.154 | 13.767 | 3.5 | 107.29 |

Table 4: Private sector hourly wages for men in Ontario, per year

| Year | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| 2015 | 67955 | 25.218 | 13.704 | 3.13 | 120.19 |

| 2016 | 67755 | 25.75 | 13.993 | 3.23 | 161.54 |

| 2017 | 69242 | 26.062 | 14.082 | 3.08 | 139.02 |

| 2018 | 68339 | 27.071 | 13.981 | 2.49 | 122.65 |

| 2019 | 69078 | 27.991 | 14.148 | 3 | 108.17 |

| 2020 | 11224 | 28.857 | 14.513 | 3 | 108.17 |

Table 5: Private sector hourly wages for women in Ontario, per year

| Year | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| 2015 | 58546 | 19.934 | 10.790 | 3 | 102.56 |

| 2016 | 58610 | 20.419 | 11.130 | 2.02 | 112.09 |

| 2017 | 58669 | 20.819 | 11.253 | 3 | 140 |

| 2018 | 57414 | 21.974 | 10.825 | 3 | 134.62 |

| 2019 | 58406 | 22.942 | 11.385 | 3.13 | 110 |

| 2020 | 9664 | 23.507 | 12.101 | 5.64 | 104.4 |

Table 6: Gender gap in average hourly wages, per year

| Year | Ontario wage gap ($/hr) | Ontario private sector wage gap ($/hr) |

| 2015 | 3.428 | 5.284 |

| 2016 | 3.474 | 5.331 |

| 2017 | 3.515 | 5.243 |

| 2018 | 3.217 | 5.097 |

| 2019 | 3.303 | 5.049 |

| 2020 | 3.81 | 5.35 |

Table 7: Difference-in-difference regression

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| female | -5.006*** | -1.922*** | -2.135*** | |

| (0.0386) | (0.169) | (0.148) | ||

| policy | 1.966*** | 1.966*** | -0.0202 | 0.137 |

| (0.0423) | (0.0423) | (0.0982) | (0.0852) | |

| policy # female | 0.208*** | 0.214*** | 0.476** | 0.413** |

| (0.0625) | (0.0625) | (0.145) | (0.126) | |

| female # Survey year | -0.00248***

(0.0000192) |

|||

| Constant | 25.67*** | 25.67*** | 25.05*** | 25.60*** |

| (0.0257) | (0.0257) | (0.0465) | (0.04)1 | |

| Fixed Effects | Marital Status,

Economic Family Type |

Marital Status,

Economic Family Type |

Marital Status,

Economic Family Type, Gender-Year |

Marital Status,

Economic Family Type, Gender-Year, Occupation |

| Observations | 654902 | 654902 | 654902 | 402036 |

Standard errors in parentheses

- p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Table 8: Difference-in-difference-in-difference regression

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| female | -6.003*** | -5.867*** | -5.549*** | -4.121*** |

| (0.0236) | (0.0231) | (0.0227) | (0.0322) | |

| policy | 1.471*** | -0.0561 | 0.0274 | 0.211*** |

| (0.0266) | (0.0430) | (0.0410) | (0.0373) | |

| treat | 0.240*** | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.0302) | (.) | (.) | (.) | |

| policy # female | -0.0306 | -0.0591 | -0.111** | -0.190*** |

| (0.0399) | (0.0391) | (0.0372) | (0.0396) | |

| policy # female # treat | 0.322*** | 0.344*** | 0.318*** | 0.354*** |

| (0.0752) | (0.0737) | (0.0702) | (0.0749) | |

| female # treat | 0.693*** | 0.561*** | 0.541*** | 0.403*** |

| (0.0447) | (0.0439) | (0.0417) | (0.0569) | |

| policy # treat | 0.418*** | 0.391*** | 0.407*** | 0.238*** |

| (0.0507) | (0.0497) | (0.0473) | (0.0505) | |

| Constant | 25.59*** | 26.15*** | 25.99*** | 25.83*** |

| (0.0158) | (0.0179) | (0.0172) | (0.0234) | |

| Fixed Effects | None | Province-Year | Province-Year,

Marital Status, Economic Family Type |

Province-Year, Marital Status,

Economic Family Type, Occupation, Education, Age |

| Observations | 2348932 | 2348932 | 2348932 | 1439864 |

Standard errors in parentheses

- p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Table 9: Difference-in-difference: Ontario private sector, per parental status

| (No children) | (Children) | |

| female | -1.516*** | -2.436*** |

| (0.207) | (0.289) | |

| policy | 0.0333 | -0.0412 |

| (0.120) | (0.168) | |

| policy # female | 0.317 | 0.683** |

| (0.178) | (0.247) | |

| Constant | 24.40*** | 26.10*** |

| (0.0567) | (0.0798) | |

| Observations | 418775 | 236127 |

Standard errors in parentheses

- p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Fixed effects: Gender-Year, Marital Status,

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| female | -1.795 | -2.489*** | -1.161 | -4.195*** | -5.206*** | -0.714 | -0.486*** | -6.118*** | -4.012** | -3.584*** |

| (1.103) | (0.352) | (1.016) | (0.671) | (0.681) | (0.861) | (0.143) | (0.804) | (1.238) | (0.465) | |

| policy | -0.801 | 0.633 | -1.011** | 1.498 | -1.475* | 0.697 | 0.485*** | 0.492*** | -1.389*** | 0.597** |

| (0.539) | (0.324) | (0.361) | (0.928) | (0.691) | (0.618) | (0.101) | (0.133) | (0.419) | (0.193) | |

| policy

#female |

0.938 | -0.331 | 0.935 | -0.565 | 2.577** | -0.613 | 0.147 | 0.799 | 2.369* | 0.141 |

| (0.874) | (0.385) | (0.751) | (0.991) | (0.795) | (0.802) | (0.134) | (0.546) | (0.950) | (0.354) | |

| Const. | 44.30*** | 27.81*** | 36.47*** | 30.24*** | 29.79*** | 23.61*** | 17.60*** | 25.06*** | 22.39*** | 23.05*** |

| (0.258) | (0.154) | (0.169) | (0.410) | (0.356) | (0.267) | (0.0477) | (0.0619) | (0.189) | (0.0894) | |

| N | 26336 | 62846 | 31969 | 18835 | 19534 | 7474 | 124241 | 69682 | 9424 | 31695 |

Economic Family Type

Table 10: Difference-in-difference: Ontario private sector, per occupation

Standard errors in parentheses

- p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Fixed effects: Gender-Year, Marital Status, Economic Family Type

Table 11: Robustness Checks: Difference-in-Difference

| (1 – Ontario Private Sector) | (2 – Ontario Private Sector) | (3- Ontario

Public Sector) |

(4 – Rest of Canada) | |

| policy | 0.178 | 0.132 | -0.217 | -0.0302 |

| (0.152) | (0.0852) | (0.235) | (0.0548) | |

| policy# Female | 0.411** | 0.417*** | 0.374 | 0.112 |

| (0.132) | (0.126) | (0.293) | (0.0774) | |

| Constant | 46.88*** | 29.84*** | 44.13*** | 34.34*** |

| (0.121) | (0.0770) | (0.150) | (0.0362) | |

| Fixed Effects | Marital Status,

Economic Family Type, Occupation, Occupation-Policy, Gender-Year |

Marital Status,

Economic Family Type, Gender-Year, Occupation-Year |

Marital Status,

Economic Family Type |

Marital Status,

Economic Family Type |

| Observations | 402036 | 402036 | 217888 | 2324514 |

Standard errors in parentheses

- p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Table 12: Difference-in-difference-in-difference, Gender Year Fixed Effects

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| female | -6.003*** | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.0236) | (.) | (.) | (.) | |

| policy | 1.471*** | -0.161** | -0.0567 | 0.0916 |

| (0.0266) | (0.0539) | (0.0513) | (0.0468) | |

| treat | 0.240*** | 0.240*** | 0.243*** | 0.00995 |

| (0.0302) | (0.0302) | (0.0288) | (0.0407) | |

| policy # female | -0.0306 | 0.176* | 0.0786 | -0.00806 |

| (0.0399) | (0.0807) | (0.0768) | (0.0701) | |

| policy # female # treat | 0.322*** | 0.318*** | 0.292*** | 0.338*** |

| (0.0752) | (0.0751) | (0.0715) | (0.0792) | |

| female # treat | 0.693*** | 0.697*** | 0.671*** | 0.568*** |

| (0.0447) | (0.0447) | (0.0425) | (0.0602) | |

| policy # treat | 0.418*** | 0.406*** | 0.416*** | 0.253*** |

| (0.0507) | (0.0507) | (0.0482) | (0.0534) | |

| Constant | 25.59*** | 23.43*** | 23.41*** | 23.98*** |

| (0.0158) | (0.0170) | (0.0162) | (0.0225) | |

| Fixed Effects | None | Gender-Year | Gender-Year,

Marital Status, Economic Family Type |

Gender-Year,

Marital Status, Economic Family Type, Occupation |

| Observations | 2348932 | 2348932 | 2348932 | 1439864 |

Standard errors in parentheses

- p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Table 13: Labor Force Survey Occupations Categories

| Column Number | Occupation |

| 1 | Management occupations |

| 2 | Business, finance and administration occupations |

| 3 | Natural and applied sciences and related occupations |

| 4 | Health occupations |

| 5 | Occupations in education, law and social, community and government services |

| 6 | Occupations in art, culture, recreation and sport |

| 7 | Sales and service occupations |

| 8 | Trades, transport and equipment operatotors, and related occupations |

| 9 | Natural resources, agriculture and related occupations |

| 10 | Occupations in manufacturing and utilities |

Occupations 2-10 exclude management occupations in these fields

Fig. 1: Average Hourly Wages, Ontario, by gender

(a) Source: Labor Force Survey, Statistics Canada

Fig. 2: Average Hourly Wage in Ontario Private Sector, by gender

(a) Source: Labor Force Survey, Statistics Canada

Fig. 3: Simplification of difference-in-difference methodology

Fig. 4: Simplification of triple difference methodology

Fig. 5: Average Hourly Wage in Private Sector, by gender and region

(a) Source: Labor Force Survey, Statistics Canada

Return to the Department of Economics website.

Scroll more news.