Imagine combining the characters of a billionaire tech founder, academics from some of the most prestigious research institutions in the world, and a cast of three thousand residents of the United States living below the poverty line. It’s not the pitch for cinematic a summer blockbuster, but a summary of the season’s hottest methodical and meticulous research study. It has captured media attention across the political spectrum.

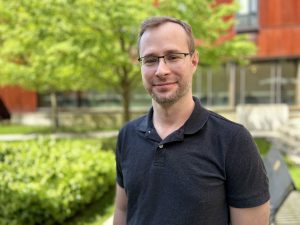

Eva Vivalt, Assistant Professor of the Department of Economics at the University of Toronto, was one of the lead researchers in a Research Practice Partnership (RPP) that spent years investigating the outcomes of unconditional cash transfers to people living in poverty.

1000 people with average annual household incomes of $29,000 living in Illinois and Texas received transfers of $1000 per month for three years. A control group of 2000 people from the same locations and income levels received $50 each per month. Described as the “Sam Altman-backed basic income study,” in the popular press since the study results came out at the end of July, $24 million of the almost $40 million in cash transfers was funded by the Altman-founded OpenAI through OpenResearch. The project was driven by Altman’s often-stated belief that some form of basic income may be necessary as AI replaces people in jobs. [Read more…]