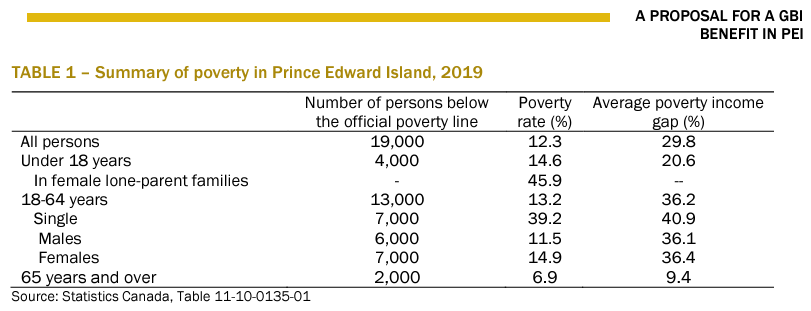

Kourtney Koebel knows how to reduce the experience of poverty on Prince Edward Island. Currently, almost 10% of the population of PEI lives in poverty, but Koebel and her colleagues believe it could be less than 2%. The solution? A Guaranteed Basic Income (GBI) demonstration project. The model Koebel and her colleagues are proposing would ensure that no Islanders live in deep poverty, a condition defined as having an income less than 75% of the official poverty line.

Koebel, a postdoctoral fellow with the Department of Economics, Arts and Sciences, University of Toronto, is part of Coalition Canada, a cross-country network of experienced basic income advocates and experts. At the end of 2023, the group released A Proposal for a Guaranteed Basic Income Benefit in Prince Edward Island. The report presents a basic income model for a fully funded 5 to 7-year long demonstration program that, according to the report, would both reduce poverty for Islanders and be more cost-effective than previous GBI models that have been proposed or piloted.

Canada Coalition chose PEI for the demonstration for its mixed economy, size, and social cohesion. Two teams, one lead by economists like Koebel, the other lead by politicians and policy makers, were both joined by GBI advocates to author the report collaboratively. The politicians helped the economists to understand Federal and Provincial financial and social parameters while the economists helped the politicians to understand modelling requirements and the financial implications of decisions. Throughout their work, the teams worked to keep each other’s contributions and goals within the “realm of the possible.”

GBI became known as a poverty alleviation strategy in Canada largely through pilot program known as Mincome conducted in Dauphin, Manitoba from 1974 to 1979. Ontario had a plan in place to implement a pilot program in Thunder Bay, Lindsay, Hamilton, Brantford and Brant County that was cancelled in 2018.

Koebel answered questions about her experience working on the report with Coalition Canada.

Question: How did you become involved with Coalition Canada?

Answer: I have been involved with the basic income community since 2016 when I completed my master’s in economics under the supervision of Robin Boadway. Robin introduced to me the concept of a guaranteed basic income and we ended up collaborating with Katherine Cuff of McMaster University on papers related to the design and financing of a GBI in Canada. It was through this work that I began to connect with academics, activists and policymakers interested in GBI. In terms of my involvement on this specific report, intially Harvey Stevens was conducting the simulations but he sadly passed away before completion of the report. Harvey taught me how to use the modelling software used to conduct these simulations, so when I was asked to complete his part of the project, I was happy to agree. The report is dedicated to Harvey, who worked tirelessly on this and many other GBI papers, and to whom I will always be grateful to for his guidance and generosity.

Q: What has the response to the report been so far? What kind of progress has it made with the PEI and federal governments?

A: There has been a pretty unanimous response from economists, public servants, politicians, and academics that the report is novel, judicious, and impressive. Team members are helping to spread knowledge of the report throughout the country via presentations and briefings in PEI and with Federal representatives and civil servants. I think the report has been very effective in rejuvenating interest in the concept of a GBI, in part due to innovative ideas in the report, its practicality, and the proposed administration of the benefit.

In terms of the impact of the report on collaborative progress between the PEI and federal governments, this has been more challenging. Issues of federalism have been some of the main implementation barriers of GBI in Canada since provinces have jurisdiction over most social and labour policies but insufficient resources to finance provincial-wide GBIs on their own. From a financing perspective, this means that some federal involvement is necessary. The report has brought the idea of a GBI into the realm of the possible, forcing politicians who are open to the idea of GBI to consider whether they are prepared to move towards the development of a federal-provincial joint demonstration project. Through the report, we have moved the discussion of GBI away from the theoretical, and into the world of difficult discussions and negotiations. This is great, but it does not ensure there will be success in getting both governments to a negotiating table.

Q: What is the most pressing piece of knowledge, or information, about GBI that you wish more people knew?

A: There are two things that I wish more people knew about a GBI. First, a GBI need not be universal in design. There are two ways to design a GBI. You can do it universally, in which every citizen receives the same amount, or it can be income-tested, in which the guaranteed benefit amount is contingent on income. The second method means that people with lower incomes receive a larger transfer than those with higher incomes, who might receive no transfer at all at very high incomes. Many people who have heard of the concept of a GBI typically have knowledge of the universal version only and are skeptical regarding the cost. However, it is possible to accomplish the goals of a universal basic income with a more targeted, and cheaper, version and we have good examples of programs in Canada that are designed in that way. For example, the Canada Child Benefit is a generous income transfer to households with children that provides larger benefits to lower- and middle-income families.

Second, the positive effects of a GBI extend beyond helping a particular individual or family. There is a large literature in economics demonstrating that complexities embedded in tax systems leads to reduced program take-up. A GBI has the potential to considerably simplify the tax and transfer system and improve the likelihood that beneficiaries receive the benefit income they are entitled to. Some have argued that lower tax-filing rates among low-income Canadians is evidence that a GBI, which would require tax filing, will not get to the people who need it most. However, the less cognitively demanding it is to navigate and apply for benefits programs, the higher the chance a low-income individual or family will receive the benefits they are eligible for. A GBI substitutes the myriad of confusing and stigmatizing federal and provincial income support programs and tax credits with a simple process and significantly reduces knowledge or information barriers for applicants. It has the potential to eliminate deep poverty, and potentially all poverty, by ensuring people get the income assistance they need in a way that a complicated network of benefits does not.

Q: What is it about GBI that puts it “in the realm of the possible” compared to other poverty alleviation tools?

A: There are many examples of successful poverty alleviation tools. For example, recently published research by Michael Baker, Derek Messacar and Mark Stabile reveals that the Canada Child Benefit, introduced in 2016, significantly reduced poverty among single and two-parent families. However, many of the existing programs are insufficient for eliminating poverty and are not necessarily used fully by those who are eligible. The GBI is believed to be relatively more effective at poverty reduction because it is income-tested rather than means-tested. It’s simpler for eligible recipients to understand, removes stigma associated with receiving welfare, and is able to provide a greater sense of dignity to recipients by providing them with financial freedom and discretion over spending.

What puts this specific report “in the realm of the possible,” is that we explicitly demonstrate that the implementation of a GBI need not be complex and that it can be done affordably by reducing the benefit based on census family income. These are important contributions to previous proposals where these considerations had not been established in a straightforward way.

Q: How Is your model different from previous GBI models?

A: This GBI report was the first developed in Canada to seriously consider political realities from the onset. The politicians on the team gave the economists a clear sense of parameters that needed consideration. We knew the proposal could not require any changes to federal tax legislation, which constrains how the GBI can be financed. It was also clear to us that financing the proposal could not require any additional tax burdens to the middle class. The politicians indicated that the estimated cost of a GBI in previous proposals was too high in terms of political feasibility and in this report, we managed to reduce the cost by roughly 40% compared to previous estimates. It was also the first proposal to present implementation suggestions and, specifically, how to address the interaction of the GBI reduction rate with those of other programs affected by the introduction of a GBI.

Q: The two-team structure you employed to author the report so that all parties could concentrate on their strengths is interesting. Did making this level of collaboration work require any special innovations or solutions for over-coming challenges in communicating with one another using two quite different vocabularies?

A: Yes, the facilitators did an excellent job maintaining communication not only across teams but also within them, as the teams were quite large and comprised of members with diverse experience and expertise. There were five different “vocabularies” to translate between: economists, public servants, politicians, advocates and facilitators. The facilitators of these teams needed to communicate frequently both with each other and with the teams – and sometimes with individual team members. They helped ensure that key issues were properly understood and determined when to bring both teams together. The facilitators needed to work very closely with each team to ensure they were both in agreement with every step and decision made in managing the teams. These conversations were not always easy and necessitated a high level of patience, cooperation and mutual respect, as well as being able to listen and hear what was said.

Another key element of this process was that everyone was a volunteer. For the facilitators, managing a group of volunteers requires a different skill set than that required to manage employees. With volunteers there is both commitment and equality.

Q: Economists, and economics research, plays a role in designing, testing, and implementing poverty alleviation strategies. Can you explain how you personally see the role of economists in poverty alleviation work here in Canada?

A: In terms of the role of economics in poverty alleviation, I believe that economists make two important contributions. First, they think deeply about trade-offs and the unintended consequences of specific policy initiatives, helping to minimize the possibility that any given policy intervention makes a potential group of intended beneficiaries worse off. Second, the causal methodologies that we use in our research allow us to evaluate government poverty-reduction initiatives rigorously and determine whether they meaningfully impact recipients or whether certain adjustments need to be made to better achieve program goals. In this sense, economists offer important insights both in terms of program development and subsequent evaluation.

Return to the Department of Economics website.

Scroll more news.